Media Contact: Carmen Ramos Chandler, carmen.chandler@csun.edu, (818) 677-2130

While the academic year winds down, Antastasiia Timmer, an assistant professor of criminology and justice studies at California State University, Northridge, said student activism over the war in Gaza is not over.

To understand what she means, Timmer said, one need only look at student protests of years past. In the 1960s, student protesters took on racial and gender injustices and called for the end of the war in Vietnam. In the 1980s, college students rallied against apartheid in South Africa.

“There is research out there about research about social movements and protests, but so often the approach is what are the benefits for the students versus the costs, and how that influences whether they are going to join a movement,” said Timmer, whose own research focuses causes of crime and violence and the trauma experienced by vulnerable populations. “So much of the research about student protests misses the point. Students join protests when they believe in the cause fully and are convinced that institutional approaches to addressing the issue are not working. And history had taught them that student protests do lead to change.”

Timmer, who teaches in the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, said student protests do not happen spontaneously. They begin, she said, with conversations in dorms and in classrooms, where they engage in discussions about what is happening in the world and how it impacts the people who live in it.

“If we, as educators, are doing our jobs, we are teaching them to think critically about what is happening and are creating safe spaces in our classrooms to discuss the issues,” Timmer said. “My opinion does not matter. What does matter is that the students are engaging in thoughtful, serious dialogue about the issues. But if they see that nothing is happening to solve the issue, that the people who are in authority are not doing anything or not moving fast enough, they can come to the decision that they need to bring more attention to the cause.”

It is in that desire to affect change that protests are born, she said.

There comes a time, Timmer said, that students become “so close their cause, that they are willing to risk something for it, whether it’s some form of discipline — a suspension or even arrested. But to the protesters, those sacrifices are little when compared to the suffering of the people they are advocating for.”

“The interesting thing is,” she said, “some studies show the riskier the protesters’ actions are, the more likely it is that more people will join them.

“It’s called ‘collective empowerment’,” she continued. “Students get inspired by what they see other students are doing. They see how others are fearless and willing to put something on the line for something they truly believe in. They want to be part of that. They know that they will be taking risks, but they also know — as history has taught them — is that when people are willing to take risks, that is when change happens.”

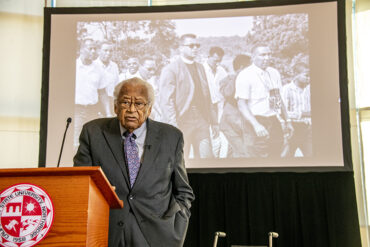

Timmer noted that most American universities celebrate the very people — from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to Cesar Chavez — the students draw inspiration from.

“For leaders of a university, honoring people like that demonstrates their commitment to ‘equality’,” she said. “But when the situation hits closer to home, possibly threatening their personal status, all of that can go out the window. It’s no longer about their beliefs in fairness, equality and the change that they hope their students will make in the world, but rather what can they do to keep things the way they are.

“You constantly hear words like ‘active participation,’ ‘diversity,’ ‘equal rights’ and ‘globally focused’ when you hear educators talk about their students and what they ultimately hope to instill in their graduates, but they don’t always put it into action in the same way when student protesters start making demands using those very same words,” Timmer said.

She noted that history has shown that decisions by university leaders to call in law enforcement to quell the student protests fail.

“There’s this belief in the U.S. and in many other countries that if we use force, people will get scared, and that fear is a big deterrent,” she said. “Well, it’s often not.

“As a criminologist,” she continued, “I can point to so much research showing that arresting and incarcerating people you disagree with often has the opposite effect. To think, ‘I’m going to call the police and the students are just going to go away’ is not going to work.”

Timmer said research demonstrates that that best way to understand student protesters involves listening and dialogue.

“The protesters are not doing what they are doing randomly,” she said. “They’ve stated their cause and made it clear what they want. Censoring their speech, heavy-handed tactics by police are not going to work. We’ve seen this with protests in years past. Student protesters don’t go away. They just regroup.

“If the protesters truly believe in their cause, you won’t crush their ideas,” she said. “They believe that no one is free until everybody is free, if you hear what they are saying. That’s a very strong belief. You can send in the police all you want, but they aren’t going to stop believing in that. They believe in freedom, and they believe in human dignity, ideals that we all hold dear. More importantly, they believe they are on the right side of history.”

Comments are closed.