Xóchitl Flores-Marcial, an associate professor of Chicana/o studies at California State University, Northridge, was reviewing 16th-century court documents from a lawsuit filed by members of the Zapotec indigenous community against their governor, in an area that is now the state of Oaxaca, Mexico.

The testimony included a detailed description of a then centuries-old tradition in which members of the community shared their goods or skills, knowing that sometime in the future the recipients would pay it back.

“The testimony provided hard evidence,” Flores-Marcial said, “that the indigenous people of the Americas for centuries before colonization had a system of collaboration, exchange and sharing, which researchers now refer to as social networks and shared economics.”

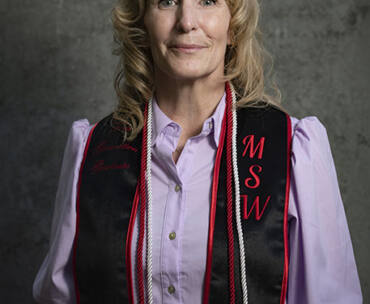

Flores-Marcial is one of a handful of scholars from around the world studying the Zapotec gift-giving practice known as “Guelaguetza.” She has been awarded a prestigious Ford Postdoctoral Fellowship to complete her book, “Zapotec Gift: Guelaguetza, Mesoamerican Social Networks 1330-2020,” which will be the first of its kind to document the Zapotec tradition.

“It’s a way of life, a code of conduct, and the reason why I recognized it in the testimony is because this tradition continues today in indigenous communities, in my community and in my own family,” said Flores-Marcial, who is Zapotec and one of only 24 American scholars to be awarded a Ford Postdoctoral Fellowship for the 2022-23 academic year.

With the support of the fellowship, Flores-Marcial will spend much of next academic year in Mexico, studying pre-Hispanic stone records and colonial paper registers and other rare documents in the archives of Museo Nacional de Antropología, and collaborating with Zapotec community leaders and Mexican historians to research Guelaguetza traditions.

She said she hopes her research will “bring to light the particular role Zapotec women had in managing crucial economic powers and social ties needed to sustain Guelaguetza through the trauma of 300 years of colonialism.”

Flores-Marcial plans to use contemporary oral testimonies to “connect this longer historical experience to the present-day use of Guelaguetza by Oaxacan immigrants,” she said, “and as a basis of the annual — and now monetized and performative — transethnic and multilingual celebrations that form the basis for Oaxaca’s international tourism campaigns.”

She said Western historians have only recently begun to recognize the impact of these traditions of indigenous people of Oaxaca.

“Because it’s not part of their traditions, it’s harder for them to recognize,” she said. “I am Zapotec, so I immediately recognized what was being talked about in the testimony. Guelaguetza is part of my own history. I recognized it in that document, and I continued to see it as I conducted further research. Having that experience made it easier for me to recognize something that other historians overlooked.”

The ideas of community and social networks, even transactional relationships, are done differently in the Western world, she explained.

“In the Western world, if I want this cup, I give you money for the cup and the deal is done,” she said.

“With Guelaguetza,” Flores-Marcial said, “you may need the cup now, and at some point 0r another you will pay me back for having given you that cup. Maybe at some point I need food, and you will pay me back that way. It’s not a one-on-one transactional experience. It’s more about being part of a community in which members of that community recognize that you are part of their community — their family, if you will — and will take care of you when you need help.”

Those transactions are recorded in a Guelaguetza exchange, from which the tradition gets its name, she said.

She noted that the pre-Hispanic material culture, such as the stone genealogical registers she has analyzed, place the Guelaguetza system back more than 2,500 years.

“It’s only recently that historians have begun to understand what these written records mean,” Flores-Marcial said. “The evidence demands that indigenous societies like the Zapotec be rightfully credited for their social, economic and cultural-intellectual developments over the course of two millennia.

“The Zapotec example provides a clear and consistent record of social responsibility and a sustainable sharing economy that we can emulate in the 21st century,” she said.

Comments are closed.