Media Contact: Carmen Ramos Chandler, carmen.chandler@csun.edu, (818) 677-2130

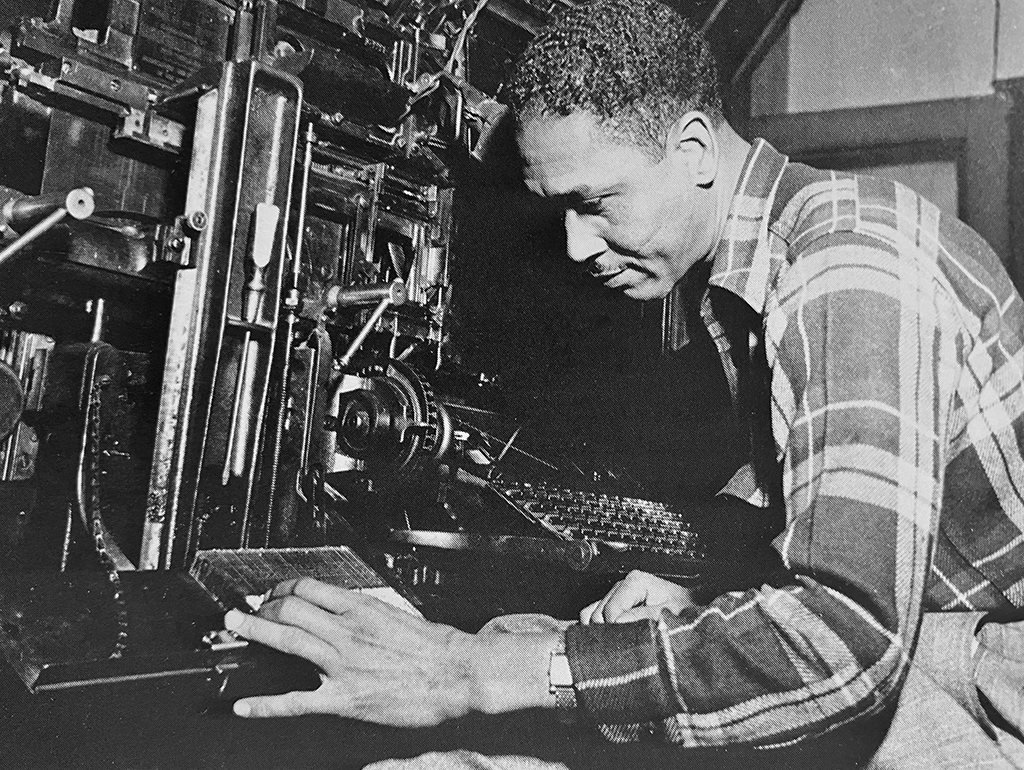

California State University, Northridge’s Tom & Ethel Bradley Center has acquired a collection of images by photographer Vera Jackson, the only woman who worked in the 1940s as a staff photographer of The California Eagle—the oldest Black newspaper in Los Angeles.

Jackson was one of five women photographers among the close to 50 photographers featured in the 1983 exhibition “The Tradition Continues: California Black Photographers,” the first and most comprehensive survey of Black photography ever exhibited in Los Angeles, curated by Lonnie G. Bunch III and Roland Charles, whose collection is also at the Bradley Center.

“We are delighted that Vera Jackson’s granddaughters trusted CSUN’s University Library and the Bradley Center to preserve and disseminate their grandmother’s collection,” said journalism professor José Luis Benavides, director of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center. “We intend to honor the legacy of Vera Jackson and promote her work among scholars, artists, students, and the larger community. Jackson was a pioneer photographer in Los Angeles and the nation.”

Charlotta Bass, the legendary publisher and editor of the Eagle, hired and assigned Jackson to work primarily with the society editor of the paper, Jesse Mae Brown. As a photojournalist, Jackson captured images of the African American elite and celebrities such as Hattie McDaniel, Dorothy Dandridge, Jackie Robinson, Philippa Schuyler, Jane McLeod Bethune, Lena Horne, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. and Hazel Scott. She also photographed families, personalities in the Black community, businesses in South Los Angeles, and political and civil rights activities in the city.

Jackson’s photographs have been exhibited at the UCLA Gallery; the Riverside Art Museum; the Black Gallery; the National Museum of Women in the Arts; the Los Angeles County Public Library; the California Museum of Afro-American History and Culture, now the California African American Museum; and the Museum of Art in San Francisco. Jackson’s work was featured in Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe’s book “Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers” and in Stanley Nelson’s documentary “The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords.”

“Vera Jackson’s images are much more than a photographic record,” Benavides said. “They are also a form of artistic expression of a pioneer photographer helping us appreciate and better understand life in Black Los Angeles.”

Vera Jackson told Moutoussamy-Ashe that “photography has enriched my life in so many ways.”

“It is my way of telling the world how I feel about the beautiful experience of living and learning,” she said. “I’d rather think I am helping to open up new horizons of the mind, rather than to just make beautiful photographs, which, of course, I am also trying to do. If it is art, all well and good, but I hope I am also brining greater understanding of how we were in the 1930s and 1940s.”

Benavides said the addition of Vera Jackson’s collection strengthens the Bradley Center’s reputation as the most important archival place for African American photography in the region.

“Her photographs will be in the rightful place, next to the center’s collections of other pioneering photojournalists of the Black press in Los Angeles like Harry Adams, Charles Williams and Jack Davis, all of whom knew and admired her work,” he said.

The curators of the 1983 exhibition of California Black photographers, Lonnie G. Bunch III and Roland Charles, wrote that Jackson’s photography represents much of the best early photojournalistic work produced.

“She shot the great and near great in her own expressionistic style,” they said. “In Jackson’s work one quickly notices the strong content of her photographs, but linger a moment, and examine how technically solid her work is as well.”

Benavides said that Jackson, like other Black photographers during the 1930s and 1940s, “elevated the morale of the Black community, built a sense of racial consciousness, counteracted the negative portrayals in mainstream media, and shaped their own image.”

“Jackson’s photographs not only reflected a woman’s perspective and artistic sensibility, but also a focus more on women in the community, documenting their work, their achievements, and their image,” he said.

She was born on July 21, 1911, as Otis Ruth, after her father, in Wichita, Kan. As an adult, she changed her name to Vera Ruth. After her mother died when she was five, her father moved to a farm in Corona, Calif., with his four children, one boy and three girls. Vera was the oldest girl. In 1936, after marrying Vernon Jackson and having two children, Kerry and Kendall, Vera enrolled in a government program to learn to use the camera, print, and enlarge.

Vera Jackson worked as a printer for freelance photographer Maceo Sheffield. Through his work for The California Eagle, she met publisher-editor Charlotta Bass, who hired her as a staff photographer, primarily for the society section of the paper. Jackson, like everybody who worked at the Eagle, felt the influence of Charlotta Bass’s commitment to fight for racial justice in a segregated city.

“I was never quite the same,” Jackson told Moutoussamy-Ashe. “None of us were after coming under the influence of Mrs. Bass. She was way ahead of her time in civil rights. She was fighting first one cause then another before it was popular to do so.”

In addition to photographing local and visiting celebrities, Jackson created featured series that uplifted the image of the community, like “The Best Dressed” and “The First Achievements.”

In the 1950s, Jackson became a teacher after receiving a bachelor’s degree from California State University, Los Angeles and a master’s degree from the University of Southern California. During her teaching years, she continued doing photography for several magazines and for exhibitions. An avid traveler, she visited different parts of Africa several times, always with a camera. She died in 1999.

The Tom & Ethel Bradley Center’s archives contain more than one million images from Los Angeles-based freelance and independent photographers between the 1930s to the present. The core of the center’s archive is a large collection of photographs produced by African American photojournalists. Oral histories, manuscripts and other ephemeral materials support the photographic collection.

The archives contain more than 70 oral histories from African American photographers, civil rights leaders and organizers, individuals involved with the history of Los Angeles, journalism, the group Mexicans in Exile and the United Farm Workers, as well as the personal papers of many individuals and organizations. The center’s Border Studies Collection examines the issues surrounding the border between the United States and Mexico.

Comments are closed.